I read Richard Adams’ Watership Down in 1978 at the age of eighteen, and for me it was, alongside The Lord of the Rings and Mrs Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, one of the influential books that shaped my dreams and imagination for a decade.

For someone who emotionally connected with anthropomorphic animal fantasy, on me it scored a direct hit. This was because it took itself deadly seriously whilst still maintaining an animal-simple world view. Life was uncomplicated, beautiful, sometimes desperate and sometimes deadly. It was the raw, vital essence of living, distilled with the complexity removed; it felt like undiluted existence Although its origins were Adams’ tale-telling to a couple of children, the final version of the story in the book of Watership Down was that of a child of nature told adult-to-adult. I have never found this vibe captured in any book I have read since – Watership Down is unique.

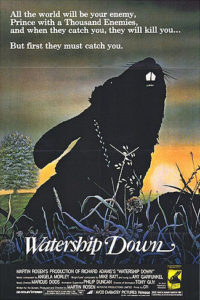

Not only did I fall for it utterly, it so chanced to happen that I travelled on holiday to England at the end of that year – the first time I, an Australian, had ever set foot in the ‘motherland’. This was a Watership bonanza for me. The movie had just been released, and as I rode on the London underground for the first time in my life, I was treated to the sight of huge posters on the walls, depicting a rabbit blackly silhouetted against the setting sun. This was a stunning image. A closer look showed, subtly placed behind the foreground plants and grasses, a wire snare around his neck strangling him to death. This vouched the production’s credentials – it would be a story that would pull no punches. When I stayed with family friends in Gerrard’s Cross, with access to strolls through the woods of Burnham Beeches (a world both alien and familiar to me), I was then finally able to go to the local cinema to watch the animated feature for the first time.

It was all I could have hoped for. They had made as good a movie of the book as anyone could have expected in the real world. I bought the picture book of the film (you couldn’t buy actual movies in those days. folks) and later the LP album of the beautiful musical score.

For the crowning glory, I took a train to Newbury and spent a day hiking from there to Whitchurch, through the heart of the actual Berkshire countryside in which Adams had set the story. And which, I may add, the film makers had painstakingly depicted, location by location, in their background art. This even included the actual building of Nuthanger Farm, a private residence that played a central part in both book and film. The down, the power pylons, the railway, the church yard, all were there. That month of my life was a thrill that will never quite be matched.

I don’t think Adams thought of Watership Down as a children’s book. But do I think the producers of the film felt compelled to market it as such or face commercial failure. As a result, we had the strange instance of the principal characters of a ‘kids’ flick’ tearing one another’s throats out and bleeding to death on screen. I think all that proves is it wasn’t really a kids’ flick.

This left parents with the uncomfortable dilemma of whether or not to take their children to it. I remember the next year, back in Australia, my aunt and uncle asking me whether I thought it would be frightening to my niece, who I think must have been about six at the time. They were concerned because she had recently watched another animal movie, ostensibly for children, from which she had come away traumatised – silent, clinging, cowering and refusing to speak. I sat her down and pulled out my picture book. I gently showed her some of the beautiful scenes of the rabbits and the countryside. And, admittedly, the fighting. And the lacerations. And suffocations. And strangulations. And exsanguinations. And… by the look on her face I reached the firm conclusion that if my little niece had been terrified by one single scene in some other animal movie, then perhaps a screening of Watership Down would not be for her.

I told my uncle and aunt it wouldn’t be a good idea to take her to the cinema. They thanked me for my counsel.

Oh, and incidentally, what was the original movie that had terrified the daylights out of her? The Tales of Beatrix Potter, as performed by the Royal Ballet. I never did find out why.

FOOTNOTES

- I was inspired to write this post in response to a segment about films that caused childhood traumas, broadcast by Nick Hodges on the excellent on-line channel History Buffs.

- Jasmine Jaegermond’s maiden name was Down. I named her after this book.